Participation welcome!

How participatory design can transform STEM programs

Carolin Enzingmüller, Jane Momme & Justus-Constantin Bahr

How diverse is STEM? Who actually connects with our educational or science communication initiatives? These are key questions when it comes to making STEM topics accessible. Too often, the focus lies solely on the results - the formats, materials, and their impact. This article makes the case for looking closer at the process leading there: the design process. If we want STEM to be more inclusive, how we design matters just as much as what we design.

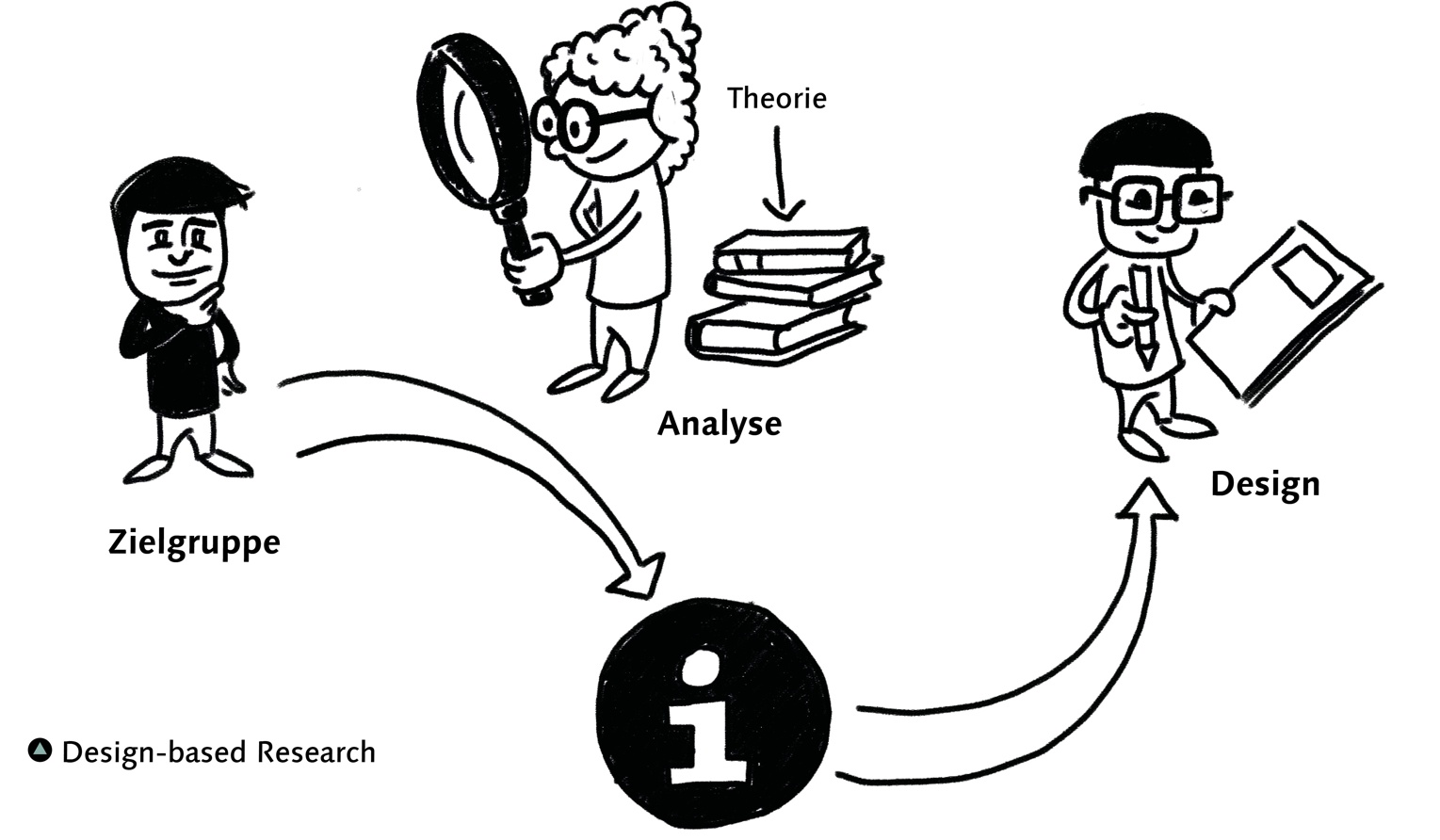

Usually, people identify with certain groups through shared experiences and affiliations. These identities significantly influence how individuals relate to services and spaces - whether they feel they belong, and whether they choose to engage. Participatory approaches such as co-design make it possible to include the identities of future users in the development process of educational and communication offers right from the start. Traditionally, design work in education often focuses on advancing theory and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions, with target groups mainly serving as sources of information. Co-design, by contrast, emphasizes active collaboration with those target groups. This shift creates more opportunities for identity formation and meaningful participation.

The potential of co-design

Co-design offers promising opportunities to make STEM initiatives more inclusive and better tailored to diverse needs. Direct dialogue with target groups - especially target groups that are underrepresented - can help to identify hidden barriers and address them in the design process. When researchers, designers, and the target groups work together, a variety of perspectives feed into the development of educational formats. By incorporating the knowledge, values, and lived realities of future users, projects can become more relevant and accessible. The process itself can challenge stereotypes and help create a more thoughtful, reflective approach. Involving people as equals can ultimately have an impact at the system level by addressing structural inequalities and rebalancing power dynamics.

What is co-design?

The term ‘co-design’ refers to a collaborative design approach that aims to actively involve various stakeholders in the development process of tools, materials or events. Instead of design decisions being made solely by experts, designers, users and other interest groups work together. The basic idea is based on the assumption that those who are affected by a product or solution should also actively participate in its design. The various perspectives are therefore integrated into the creative process using methods such as workshops, interviews or prototype tests.

Challenges: Who participates?

As promising as participatory approaches such as co-design are, they come with real challenges. Research shows that achieving truly equitable participation is not easy and, in some cases, poorly designed processes even reinforce existing inequalities. In addition to challenges such as navigating expectations, roles, feedback and strategic priorities, co-design processes require significant flexibility, openness, time, and resources. Barriers already begin at the stage of recruiting participants: Issues of accessibility, language, and socio-cultural and epistemic differences can remain invisible but still shape who feels welcome – or excluded. Furthermore, most educational and communication systems reflect Western values and knowledge structures, which can make participatory approaches seem elitist or irrelevant, especially to underrepresented groups. That is why it is not enough to simply offer participatory formats - they must be carefully designed to reflect on, and ideally remove, barriers.

What does research say about co-design?

Numerous studies confirm the positive effects of the co-design approach. Meta-analyses in the field of software development, for example, show that the involvement of target groups can lead to greater satisfaction and stronger identification with the end product. Users also perceive the offerings as more relevant and accept them better. Furthermore, research findings show that co-design approaches increase creativity and innovation in development processes by introducing new ideas and perspectives. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms remain complex and are heavily dependent on organisational, project-related and user-related factors. Well thought-out target group involvement is therefore of crucial importance.

Conclusion: Five recommendations for getting started

Despite the challenges, co-design is well worth considering. Here are five recommendations to help you get started:

Check the fit: First, ask whether co-design makes sense for your project. Not every initiative requires – or can afford – full-scale participation. Sometimes, smaller steps like short surveys or feedback rounds can already help align with your target group.

Start small: Participation in the design process does not have to begin with a big effort. A single workshop early in the process can already reveal potential barriers and help clarify the needs of your target group.

Plan thoughtfully: Ideals are important, but your approach needs to match your resources. There is no one-size-fits-all in co-design - adapt your process to your specific context. Seeking advice from experiences practitioners can especially helpful if you are just starting out.

Value time and ideas: Participants' time is valuable. Show appreciation through financial compensation or opportunities for personal or professional development. Be clear from the start about copyright and usage rights, too.

Avoid participation-washing: Participation is currently trending and increasingly being promoted. If you promote your initiative as participatory, make sure people are genuinely involved in decision-making and can see how their input shaped the outcome.

Co-design is not a cure-all for STEM, but it opens up new possibilities. At its heart is a commitment to seeing and involving the people we are designing for - to take their experiences, knowledge, and identities seriously and integrate them into the design process. It takes openness and intention but it can lead to programs that that truly resonate.

About the authors:

Dr. Carolin Enzingmüller is part of the leadership team at the Kiel Science Communication Network, a transdisciplinary research center for science communication at the IPN Kiel. Her work focuses on collaborative design processes and their potential for science communication and education.enzingmueller@leibniz-ipn.de

Jane Momme is a PhD student at the Kiel Science Communication Network. There she is investigating how the participation of target groups in the science communication process affects trust in science. momme@leibniz-ipn.de

Justus-Constantin Bahr is a student assistant in the Kiel Science Communication Network and supports research on participatory science communication. He is studying psychology, geography and social sciences at Kiel University.

Further literature:

Enzingmüller, C., & Marzavan, D. (2024). Collaborative design to bridge theory and practice in science communication. Journal of Science Communication, 23(2), Y01. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.23020401